휘트니뮤지엄 해리 스미스 개인전 'Fragments of a Faith Forgotten: The Art of Harry Smith'

FIRST MAJOR EXHIBITION ON ARTIST HARRY SMITH DEBUTS AT THE WHITNEY MUSEUM

Opening October 4, 2023, Fragments of a Faith Forgotten: The Art of Harry Smith brings to life the sights and sounds of Smith’s cosmological world that transformed American culture.

New York, NY, August 3, 2023 — Fragments of a Faith Forgotten: The Art of Harry Smith, on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art from October 4, 2023, through January 2024, is the first solo exhibition of artist, filmmaker, musicologist, collector, and radical nonconformist Harry Smith (1923–1991). Best known for his compendium of song recordings, the Anthology of American Folk Music, Smith helped establish the popularization of folk music in the 1960s. This major exhibition introduces Smith’s life and work within a museum setting for the first time through paintings, drawings, designs, experimental films, sound recordings, and examples of Smith’s collecting. Designed in partnership with artist Carol Bove, Fragments of a Faith Forgotten proposes new ways of experiencing twentieth-century American cultural histories.

“At the Whitney, we strive to create exhibitions that are as innovative as the artists they present,” said Scott Rothkopf, Nancy and Steve Crown Family Chief Curator and incoming Alice Pratt Brown Director of the Whitney Museum. “Fragments of a Faith Forgotten is one such show, bringing to life the visionary world of Harry Smith as a total installation brilliantly conceived by the artist Carol Bove.”

This exhibition traces Smith’s life alongside his art and collections of overlooked yet revealing objects, such as string figures and paper airplanes gathered on the streets of New York. Fragments of a Faith Forgotten follows Smith from an isolated Depression-era childhood in the Pacific Northwest, where he was immersed in esoteric religious philosophies and Native American ceremonies, through a Bohemian youth of pot, peyote, and intellectual community in postwar Berkeley. It traces his encounters with bebop and experimental cinema in San Francisco to a decades-long residence in New York City, where he maneuvered to the center of the avant-garde fringe with Allen Ginsberg, Jonas Mekas, Patti Smith, Lionel Ziprin, and more.

Keenly attuned to the changing technologies of the day, Smith embraced innovation and used whatever was new and of the moment. At the same time, he was always in dialogue with history, and his lifelong interests in abstract art, metaphysics, spiritualism, folk art, and music from around the globe came to the fore as he devised ingenious ways of collecting sounds and creating films. These concerns make his practice increasingly prescient, as collecting, consuming, and sharing media continue to shape culture in the twenty-first century.

“Vitally, Harry Smith brought to light and wrestled with—sometimes imperfectly—facets of America’s rich histories, tracing and sharing underappreciated veins of culture often invisible to mainstream society,” said Elisabeth Sussman, Curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art. “Smith followed his own path through American culture, revealing more about this country, its arts, and its diverse creative communities than nearly any other artist of his time.”

This exhibition is co-organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts at Harvard University, where a version of the project will open in November 2024. The exhibition is curated by artist Carol Bove; Dan Byers, the John R. and Barbara Robinson Director of the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts; Rani Singh, Director of the Harry Smith Archives; Elisabeth Sussman, Curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art; with Kelly Long, Senior Curatorial Assistant, and McClain Groff, Curatorial Project Assistant, at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

EXHIBITION OVERVIEW — FRAGMENTS OF A FAITH FORGOTTEN: THE ART OF HARRY SMITH

The exhibition brings together surviving fragments from Smith’s influential work as a painter, filmmaker, folklorist, ethnomusicologist, and collector in an immersive environment designed by Bove. Distilling his remarkable and varied production into distinct sculptural spaces, Fragments of a Faith Forgotten highlights Smith’s curiosity about the cosmic and occult that he shared with mid-century Bay Area and Beat poets, filmmakers, writers, and artists. Smith’s early paintings, hand-painted abstract films, film of Seminole textiles, and Andy Warhol’s Screen Test of Smith are presented alongside stills from the liner notes of the Anthology of American Folk Music and many other works.

The Zig-Zag

Organized chronologically along a zig-zagging passageway, this section features drawings, paintings, prints, films, ephemera, and found objects that represent the depth and breadth of Smith’s idiosyncratic practices of making and collecting from the 1940s to the 1970s. These works illuminate Smith’s connections to regions of the country that were meaningful throughout his life and express his belief in the interconnectedness of different cultures, people, and ideas. After a period of self-directed research among the Lummi and Salish peoples of the Pacific Northwest and a brief stint studying anthropology at the University of Washington, Smith relocated to Berkeley in the mid-1940s, followed by San Francisco, where he joined a small circle of avant-garde filmmakers. Though he didn’t yet own a camera, Smith was inspired to develop his own filmmaking techniques—among them, hand-painting directly on film stock and using stop-motion collage to animate images on the screen, as seen in Film No. 1: A Strange Dream (c. 1946–48). In 1951, Smith moved to New York at the encouragement of Hilla Rebay, the first director of what is now the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, where he experimented with abstraction and mysticism in painting.

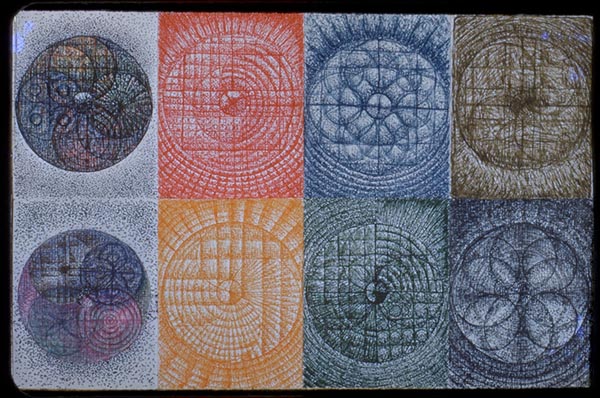

The Pinwheel

In this section, visitors encounter lightbox projections of Smith’s “jazz” paintings, in which the artist visually transcribed recordings by jazz musicians Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, and Charlie Parker onto his canvases, each brushstroke corresponding to a single note or chord. Smith considered this practice a new art form, where painting could act as both performance and instruction, anticipating the first modern graphic scores by composers such as John Cage and Morton Feldman. Smith went on to explore the methodology of these paintings in Film No. 11: Mirror Animations (c. 1957), also on view in the exhibition, through the synchronization of the animation with music. The “jazz” paintings from the late 1940s and early 1950s are today preserved solely through rare slide photographs, the originals evidently discarded by an aggrieved landlord in 1964.

Film No. 12: Heaven and Earth Magic Feature

A small black box theater immerses visitors in Smith’s Film No. 12: Heaven and Earth Magic Feature (c. 1957–62), which animates an array of cut-outs from nineteenth-century books and department store catalogues to craft a dreamlike experience of spiritual transformation. Smith relied on stop-motion animation to create the work, resulting in a new, experimental approach to imagery and storytelling. Rejecting conventional narrative, the film depicts a woman’s dental procedure for a toothache, her subsequent ascension to heaven, and finally, her return to earth. Originally a six-hour work, Heaven and Earth Magic Feature survives in a one-hour-long version and is paired with the only soundtrack Smith ever composed himself, assembled through stock sound effects in a kind of collage. Smith’s use of Rubin’s vase—a silhouetted depiction of a vase whose negative spaces form the illusion of two profiles facing one another—as an image in the film inspired Bove’s sculpture, Vase/Face, also on view nearby in the exhibition.

Film No. 18: Mahagonny

Smith’s rarely-seen magnum opus, Film No. 18: Mahagonny, is an epic, four-screen translation of Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht’s 1930 political-satirical opera Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny. Shot from 1970 to 1972 and edited for the next eight years, Smith’s two-hour-long film creates a portrait of urban America with a mesmerizing, hectic, and repetitive showcase of four films presented simultaneously while the opera soundtrack plays at high volume. Mahagonny spotlights the Chelsea Hotel in New York, where Smith lived from 1968 to 1977, and features notable avant-garde figures such as Allen Ginsberg, Jonas Mekas, and Patti Smith. These appearances are intercut with shots of New York City landmarks like Central Park and Times Square, as well as artworks from Robert Mapplethorpe’s studio and Smith’s own animations. The film merges scenes from Smith’s world with recognizable symbols of nature and humanity that he intended to be universally accessible. Smith designed a synchronized multi-screen projection system and envisioned fanciful modes of display for the work, including projecting it onto a boxing ring—a reference to the original set of Weill and Brecht’s opera.

Anthology of American Folk Music

Finally, the exhibition offers a unique listening environment where visitors can explore the multi-volume Anthology of American Folk Music. Smith’s Anthology, first released by Folkways Records in 1952, marks his unparalleled efforts to preserve American song as both art and artifact. He divided the Anthology into three sets of two LPs, entitled “Ballads,” “Social Music,” and “Songs,” each accompanied by a comprehensive booklet of notes and illustrations. As Smith would later reflect, “The whole Anthology was a collage. I thought of it as an art object.” The eighty-four songs on the compilation were made between 1927, when electronic recordings made accurate music reproduction possible, and 1932, when the Great Depression halted recordings. By including songs that displayed distinct regional qualities and had been produced for local communities rather than broader national audiences, the Anthology brought together music that may otherwise have remained out of reach to many listeners.

Smith’s Anthology became a pivotal influence on the folk music revival of the 1950s and 1960s, inspiring artists like Bob Dylan, Jerry Garcia, and Pete Seeger, and has since achieved cult status among many musicians and listeners. Upon receiving the Chairman’s Merit Award at the 1991 Grammy Awards for his contribution to the preservation and promotion of American folk music, Smith noted, “My dreams came true…I saw America changed through music.” Today, Smith’s enduring legacy continues to influence artists, musicians, and filmmakers such as Bove, Nick Cave, Joel Coen, Rufus Wainwright, and Terry Winters, among many others.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Harry Smith (b. 1923, Portland, Oregon; d. 1991, New York, New York) was an artist who delved into multiple disciplines in a quest to understand the structure and essence of what he considered universal patterns, and whose activities and interests put him at the center of the mid-twentieth-century American avant-garde. Although best known as a filmmaker and musicologist, he frequently described himself as a painter. Smith had a lifelong interest in the occult and esoteric fields of knowledge, leading him to speak of his art in alchemical and cosmological terms. His broad spectrum of interests and voracious appetite for information resulted in a number of remarkable collections of objects, ranging from records and Seminole textiles to string figures and Ukrainian Easter eggs, as well as the largest known paper airplane collection in the world.