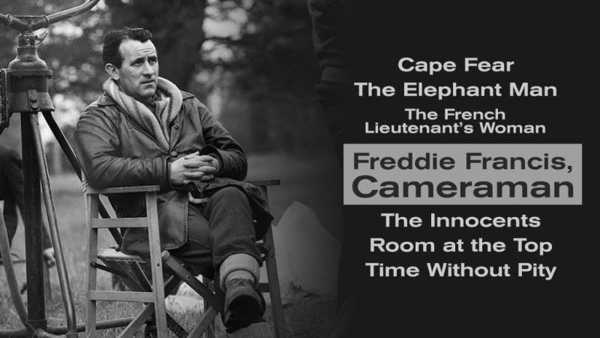

'엘리펀트맨' '케이프 피어' 촬영감독 프레디 프란시스 회고전 'Freddie Francis'@메트로그라프(5/16- )

FREDDIE FRANCIS, CAMERAMAN

Beginning May 16

Metrograph In Theater

An Array of Films Showcasing the Diverse Talents of the Celebrated Cinematographer, Including the New 4K Restoration of THE ELEPHANT MAN, THE FRENCH LIEUTENANT'S WOMAN and TIME WITHOUT PITY on 35mm, and more

Metrograph presents Freddie Francis, Cameraman, a six-film program showcasing Francis's wide range of talents, beginning May 16 at Metrograph In Theater.

“I don’t know where this cinematographer Freddie Francis sprang from. You may recall that in the last year just about every time a British movie is something to look at, it turns out to be his.” —Pauline Kael, The New Yorker

With Douglas Slocombe and Jack Cardiff, both born in the 1910s, Freddie Francis completes the Holy Trinity of English cinematography, his career stretching from the dawn of the British New Wave (Room at the Top, The Innocents) and the heyday of Hammer horror to—after a lengthy interlude to focus on his own work as a director—eye-popping collaborations with Martin Scorsese, Karel Reisz, and David Lynch. With a new 4K restoration of Lynch’s The Elephant Man now available—Francis’s first credit as DP after a 17-year hiatus, and a triumphal comeback—we’re seizing the opportunity to take an awed look at an array of films showing off Francis’s abundant gifts as a generator of onscreen atmosphere, equally adept at clammy Gothic grisaille, drab kitchen-sink realism, and lush, semi-tropical delirium.

Titles include Cape Fear, The Elephant Man, The French Lieutenant’s Woman, The Innocents, Room at the Top, and Time Without Pity.

CAPE FEAR

dir. Martin Scorsese, 1991, 82 min, DCP

Scorsese’s baroque remake of J. Lee Thompson’s 1962 potboiler of the same name about a defense lawyer terrorized by a former client improves on its inspiration in almost every regard, not least in replacing Gregory Peck as the original’s upstanding attorney with Nick Nolte, playing a far more compromised version of the same character. Add to this Robert De Niro as the film’s self-styled Übermensch psychopath, Juliette Lewis as Nolte's character’s hormonally confused daughter, a brooding adaptation of the original Bernard Herrmann score courtesy of Elmer Bernstein, and Old Master Francis’s lurid cinematography, and you’ve got one of the most distinctive thriller/morality tale/revenge tragedies of the ’90s. Of bringing Francis on board, Scorsese would say “the main thing was Freddie’s understanding of the concept of gothic atmosphere… He understands the obligatory scene of a young maiden with a candle walking down a long hall towards a door. ‘Don’t go in that door!’ you yell, and she goes in. Every time, she goes in.”

THE ELEPHANT MAN

dir. David Lynch, 1980, 124 min, 4K DCP

Directing his first feature in 1962, Francis hadn’t been credited as a cinematographer for 17 years when he made his triumphant return as DP for Lynch’s sophomore feature, one of the great black-and-white films of the ’80s or, indeed, of any decade, in which Francis conjures up a gaslit, cobblestoned Victorian London of our collective dreams and nightmares. John Hurt and Anthony Hopkins are remarkable as, respectively, John Merrick, the young man whose deformities mask a soul of unusual delicacy, and Frederick Treves, the surgeon who helps to restore Merrick’s dignity, but Francis’s contribution is no less vital. “It got down to two names, so we decided to flip a coin,” Lynch would remember of the film’s pre-production. “Freddie lost the toss. We looked at each other and said, ‘No, no, no, it’s got to be Freddie!’”

The 4K restoration of the original camera negative, overseen by director, David Lynch.

THE FRENCH LIEUTENANT’S WOMAN

dir. Karel Reisz, 1981, 124 min, 35mm

Meryl Streep and Jeremy Irons play two modern-day actors who, while filming an adaptation of John Fowles’s Victorian era-set novel of forbidden romance, The French Lieutenant’s Woman, begin an affair of their own that curiously echoes the events of the novel, each performer disappearing increasingly into their roles. Adapting Fowles, screenwriter Harold Pinter ingeniously devised the film’s parallel narratives as a cinematic equivalent to the novelist’s postmodern take on the Victorian novel, while Francis and production designer Assheton Gorton work in tandem to create a ravishing, idealized vision of the period, pre-Raphaelite painting being one vital visual reference.

THE INNOCENTS

dir. Jack Clayton, 1961, 100 min, 4K DCP

The deep focus black-and-white CinemaScope photography of Freddie Francis establishes the feeling of a terrible, lucid dream in Clayton’s adaptation of Henry James’s celebrated psychological horror tale “The Turn of the Screw,” starring Deborah Kerr as a governess who finds herself harassed by supernatural visions while minding two young children in a remote manse. One of the most frightening haunted house stories ever made, and an influence on John Carpenter’s Halloween, among countless other films.

ROOM AT THE TOP

dir. Jack Clayton, 1959, 117 min, DCP

The opening shot of the British New Wave and the defining work of so-called “kitchen-sink realism,” Clayton’s wrenching romantic melodrama sets its scene in a Yorkshire still very much in the grips of a calcified English class system and postwar austerity, starring Laurence Harvey as an ambitious working class lad with dreams of upward mobility who simultaneously pays court to his boss’s daughter (Heather Sears) and carries on a tempestuous affair with an unhappily married Frenchwoman 10 years his senior (Simone Signoret). “Freddie Francis’s cinematography is extraordinarily good… he contrives some tremendous closeup compositions of people’s faces looming disturbingly out of the screen in foreground and background, years before Brian De Palma’s ‘split diopter’ lens effects in movies like Carrie.” —The Guardian

Room at the Top was restored in 2k by the BFI in 2019 for its 60th Anniversary.

TIME WITHOUT PITY

dir. Joseph Losey, 1957, 85 min, 35mm

An impassioned protest against capital punishment, still decades away from abolition in the United Kingdom when Time Without Pity was released, this taut thriller by American blacklist refugee Losey—credited onscreen for the first time since leaving the States—stars Michael Redgrave as a recovering alcoholic who, back in England after a stay at a Canadian sanitarium, has only 24 hours in which to prove his son, slated to be executed by the state for his girlfriend’s murder, is in fact innocent… all while trying not to fall off the wagon. Only Francis’s second film as a cinematographer, and one that finds the full range of his talent already much in evidence, Time Without Pity helped re-establish Losey’s reputation—and also introduced Francis to cast member Peter Cushing, whom he would go on to direct in eight films.

Print courtesy of BFI National Archive

'정사' '붉은 사막'의 배우 모니카 비티 회고전 'Monica Vitti: L...

'정사' '붉은 사막'의 배우 모니카 비티 회고전 'Monica Vitti: L...