SP: On December 31, 2019, BTS lit up Times Square with a New Year’s Eve performance. Just weeks later, Parasite swept four categories at the Academy Awards. As a film major and journalist who moved to New York in 1996 to watch and write about movies, I was thrilled. Seeing a Korean film win both the Palme d’Or and the Oscar was a proud and emotional moment. The acceptance speeches by Bong Joon-ho and Miky Lee—full of humor, warmth, and insight—beautifully captured the Korean spirit.

Still, I felt that the contributions of Koreans in high culture were often overlooked amid the excitement surrounding the Korean Wave. While covering art museums, classical music, opera, ballet, and jazz in New York, I saw many Korean artists doing extraordinary work. I wanted to document this cultural movement beyond the spotlight of BTS, Parasite, and Squid Game.

Korean artists, once seen mainly as entertainers, had become central figures in global culture. From K-pop, film, and TV to food, classical music, ballet, beauty, fashion, sports, and gaming, Hallyu had grown into a powerful global force. As I observed this transformation, I kept asking myself: How did this happen? Who are Koreans?

A month after the Oscars, New York went into lockdown. As the writer behind NYCultureBeat (www.NYCultureBeat.com), I could no longer visit museums, concert halls, or theaters. While staying home, I began researching and writing about the roots of Hallyu.

Q: Why 33 codes?

SP: On December 31, 2011, I left The Korea Daily New York (JoongAng Ilbo) and launched NYCultureBeat on March 1, 2012. Leaving a secure job felt like a personal declaration of independence—echoing the spirit of Korea’s March 1st Movement and its 33 signatories. I was also drawn to the rhythm and symbolism of “three-three” (sam-sam, 삼삼하다). Later, I realized that my first edited book, The Movie That Changed My Life (1990), had 33 contributors, and I had moved to New York at age 33. It felt meaningful—almost like it was meant to be.

Q: How does the English edition differ from the Korean one?

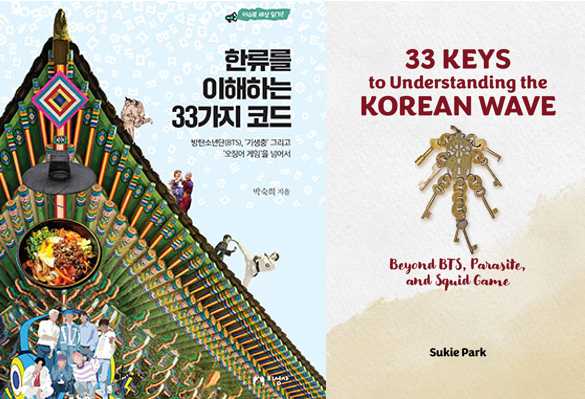

SP: The Korean edition, 한류를 이해하는 33가지 코드, published by Jisungsa in 2023, includes many color photos and spans 512 pages. The English edition (530 pages) focuses more on text and has been updated to reflect recent developments in Hallyu. I’m grateful that the Korean version is now held in university libraries such as Harvard, Columbia, Princeton, Stanford, Chicago, UC Illinois, Washington, Toronto, and Leiden University in the Netherlands.

Q: What advantages did writing a Hallyu book as a New Yorker offer?

SP: As someone who left Korea but found a second home in New York, I was able to observe Korean culture with both distance and affection. In Korea, I worked in pop culture journalism; in New York, I gradually immersed myself in high culture—attending opera at Lincoln Center, concerts at Carnegie Hall, and exhibitions at the Met and MoMA. Having never seen an opera or ballet before moving here, New York became a kind of cultural classroom for me.

Many artists aim to make their mark in New York. Beyond K-pop and K-cinema, Korean performers in classical music, opera, and ballet have earned global recognition. That broader view helped me reflect on Korea’s cultural growth with more perspective.

One lasting memory was seeing Apple’s “Think Different” billboard in Times Square early in my time here. It symbolized how this city values originality. Small moments—like a Met curator giving me a thumbs-up for photographing from an unusual angle—reminded me that New York rewards new ways of seeing. That spirit flows through this book.

Q: Did your experiences in Korea and New York help in writing the book?

SP: There’s a Korean saying, “Dig one well deeply” (한 우물을 파라), but I’ve always followed my curiosity. After graduating from Ewha Womans University with a degree in journalism and broadcasting, I explored many paths.

As a teenager, I listened to American pop music constantly, which sparked my interest in global culture. I began as a reporter at a photography magazine, then joined a pop culture magazine during the rise of Korean pop in the late 1980s. I interviewed artists like Lee Sang-eun, Park Nam-jung, Kim Wan-sun, and Lee Moon-se, as well as actors including Choi Jin-sil, Kim Min-jong, and a young Lee Jung-jae. I also met Lee Soo-man (SM Entertainment) at his café in Songdo, visited Lee Sun-hee and Sobangcha at home, and traveled to Jeju Island for a photo shoot with Lee Sang-eun. Those early experiences gave me a front-row seat to Korea’s evolving entertainment industry.

Later, I transitioned into film journalism, joined Daewoo Video’s marketing department as a copywriter, and managed public relations. I also pursued graduate studies in film at Hanyang University. During this time, I wrote scripts for KBS’s Film Music Salon and MBC’s Departure! Video Journey, although I was unable to complete my master’s thesis due to work commitments.

In 1996, I came to New York for what I thought would be just one year. In Korea, my career path was sometimes seen as scattered, but in New York, people described it as an “amazing journey.” That change in perspective helped me stay. I studied entertainment business at Baruch College (CAPS), taking classes in screenwriting, music business, and entertainment law. Seeing K-pop artists now topping the Billboard charts is especially meaningful, since Billboard was once part of my coursework.

Working at small Korean-language outlets in New York gave me the opportunity to cover a wide spectrum of the arts—visual art, classical music, opera, jazz, film, theater, and dance—and to interview Korean artists gaining recognition in the mainstream.

Koreans have made groundbreaking strides across various cultural fields. The Metropolitan Opera’s first Asian leads were Korean: soprano Hei-Kyung Hong and tenor Wookyung Kim. Hee Seo became the first Asian principal dancer at the American Ballet Theatre. Yunchan Lim made history as the youngest winner of the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition. The New York Philharmonic now boasts more than a dozen Korean musicians.

In theater, Young Jean Lee became the first Asian American woman to have a play produced on Broadway. Eun Sun Kim was named the first female music director of the San Francisco Opera. Min Jung Kim became the first woman to direct the Saint Louis Art Museum. Sonya Chung now leads Film Forum—its first new director since 1972.

In literature, Han Kang became the first Asian female writer to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. Korean-American novelist Susan Choi and poet Don Mee Choi both won the prestigious National Book Awards.

Even in the culinary world, Korean talents continue to shine. At the 2013 James Beard Foundation Awards—often called the “Oscars of Food”—David Chang won Outstanding Chef, while Danny Bowien, a Korean adoptee, was named Rising Star Chef. I was there covering the ceremony at Lincoln Center—and I was thrilled.

I also wanted to highlight pioneers like Grandmaster Jhoon Rhee, who opened a taekwondo studio in Washington, D.C., in the 1960s and taught figures such as Joe Biden, Bruce Lee, and Muhammad Ali. And Willa Kim, a two-time Tony Award-winning costume designer, left a lasting mark on American theater, dance, and opera. Their stories remind us that Korean culture was quietly taking root in the United States long before the word Hallyu entered the global vocabulary.

Q: What challenges and contributions have Korean Americans made in the arts and culture?

SP: In interviewing second- and third-generation Korean American artists, I often sensed the challenges they faced—struggles with identity, generational divides, and tension between personal aspirations and parental expectations. Many dreamed of becoming actors, filmmakers, musicians, or chefs, but their immigrant parents, focused on financial security, often encouraged more traditional paths in medicine, law, or academia. With few cultural role models—perhaps only Bruce Lee coming to mind—the gap between generations felt even wider.

Over time, some of these young creatives became “boomerang kids”—returning to their passions after initially following their parents’ wishes. Many went on to build successful, meaningful careers in the arts.

One reason I founded NYCultureBeat was to provide time-strapped Korean Americans with accessible cultural information and to spotlight Korean achievements in the arts and culinary fields. I hoped this visibility might encourage parents to better understand and support their children’s dreams.

I also met many Korean adoptees flourishing in areas like opera, ballet, musical theater, and fine dining—fields where both Korean Americans and adoptees have made a strong impression. I see their accomplishments as branches of the same cultural tree, and I felt it was important to share their stories too.

Q: What unique perspective does this book offer?

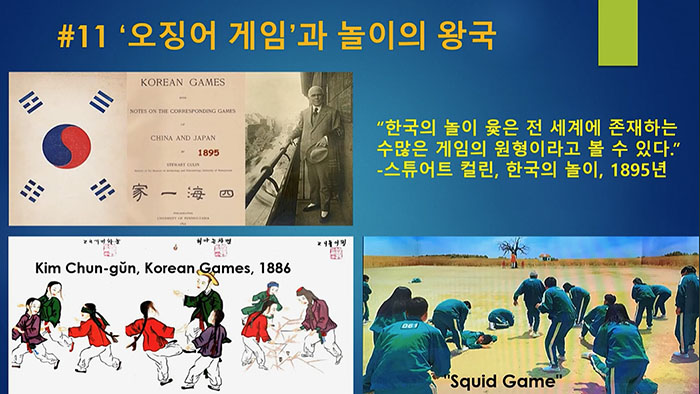

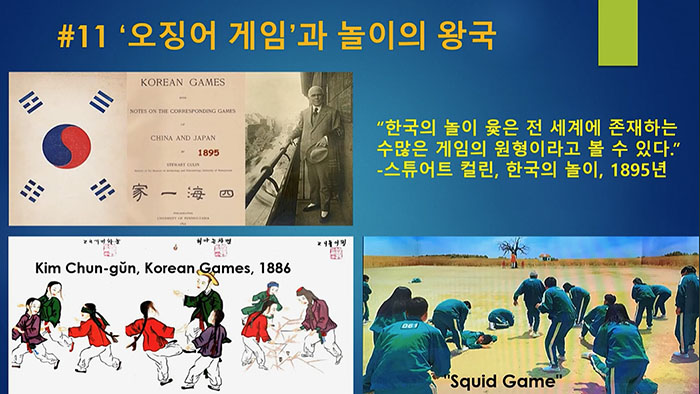

SP: In the late 19th century, Korea was known as “the Hermit Kingdom” and “The Land of the Morning Calm.” Today, Koreans are known for being energetic, innovative, and globally engaged. To understand this transformation, I explored key cultural traits such as han, nunchi, ppalli-ppalli, satire, resistance, Hangeul, metal chopsticks, kimchi, gochjang, bibimbap, resilient women, and traditional games.

I also drew connections between East and West—King Sejong and Leonardo da Vinci, Psy and Charlie Chaplin, BTS and the Beatles, mukbang and Andy Warhol’s pop art. I included voices like Father Norbert Weber, Stewart Culin, Homer Hulbert, and Pearl Buck, who recognized the richness of Korean culture long before it became globally known.

Q: How long did it take to write the book?

SP: I didn’t set out to write a book at first. During the pandemic, when I couldn’t cover cultural events in person, I started sharing my research as a column on NYCultureBeat. Writing began shortly after the 2020 Oscars and took about two years. The Korean edition came out in June 2023, and I updated and expanded the English edition afterward.

Q: Who should read this book?

SP: Anyone curious about Korean identity and culture—Hallyu scholars, second- and third-generation Koreans, adoptees and their families, and global fans. While writing, I often reflected on the creativity, passion, and resilience Koreans have shown throughout history. I hope readers will come away with a deeper appreciation for the cultural foundations behind today’s Korean Wave.

*33 Keys to Understanding the Korean Wave: Beyond BTS, Parasite, and Squid Game

(Updated English Edition) Coming Soon!

https://www.nyculturebeat.com/?document_srl=4144298&mid=Zoom

*Voices on Korea: From the Land of the Morning Calm to the Korean Wave

https://www.nyculturebeat.com/index.php?mid=Zoom&document_srl=4147788

*An Expanded Table of Contents of 33 Keys to Understanding the Korean Wave

https://www.nyculturebeat.com/index.php?mid=Zoom&document_srl=4148799