33 Keys to Decoding the Korean Waves

#29 The Rise of K-Art: Dansaekhwa, Korean Monochrome Painting

*한류를 이해하는 33가지 코드 #29 단색화의 부활과 K-Art의 부상 <Korean version>

https://www.nyculturebeat.com/index.php?mid=Focus&document_srl=4089137

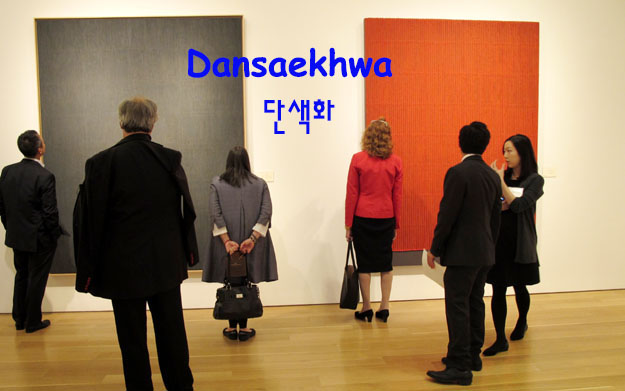

Park Seo-Bo's works, Forming Nature: Dansaekhwa Korean Abstract Art, 2015, Christie's New York Photo: The Korea Society

Korean masters of monochrome painting, called Dansaekhwa, who created artworks under Korea’s dictatorship in the 1970s, are attracting global attention for the first time in over 40 years. The late Park Seo-Bo, the late Yun Hyong-Keun, the late Chung Chang-Sup, Chung Sang-Hwa, and Ha Jong-Hyun, the five masters of monochrome painting, lead the K-Art Korean Wave. This is the generation that was born during the Japanese colonial period, went through liberation, the Korean War, military dictatorship, the democratization movement, and the digital age. If China’s Ai Weiwei and Japan’s Yayoi Kusama are modern Asian star artists, the Korean monochrome painters are the “Korean Galaxy” newly discovered and celebrated in the current art world.

#K-ART: Monochrome Painting Craze in America

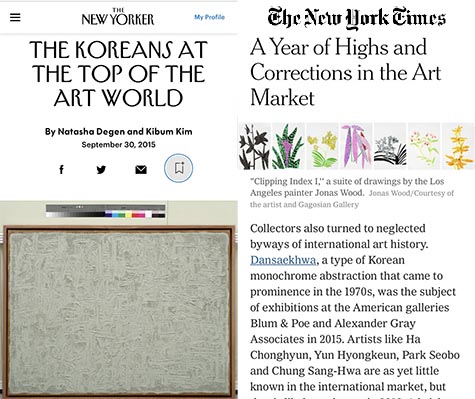

In September 2015, the weekly New Yorker magazine featured the rise of Korean monochrome painting in an article, “The Koreans at the Top of the Art World.” The New Yorker reported that Korean monochrome painting is suddenly attracting attention amid recent trends in the global art world, including the expansion of branches of major art galleries internationally, art collectors becoming more powerful due to the economic boom, and museums beginning to discover undervalued artists. Alexandra Munroe, curator of the Guggenheim Museum, who oversaw the retrospective exhibition of the Korean artist Lee Ufan in 2011, likened it to a “perfect storm.”

The New York Times also reported on trends in the global art world (“A Year of Highs and Corrections in the Art Market”) in early January 2016 and mentioned the return of the monochrome painting movement in Korea in the 1970s, writing:

“Collectors also turned to neglected byways of international art history. Dansaekhwa, a type of Korean monochrome abstraction that came to prominence in the 1970s, was the subject of exhibitions at the American galleries Blum & Poe and Alexander Gray Associates in 2015. Artists like Ha Chong-Hyun, Yun Hyong-Keun, Park Seo-Bo and Chung Sang-Hwa are as yet little known in the international market, but that is likely to change in 2016. A brick-red monochrome from 2005 by Chung Sang-Hwa, whose works evoke Yves Klein, sold for a new high of about $1.1 million with fees at a sale in Hong Kong by Seoul Auction in October.”

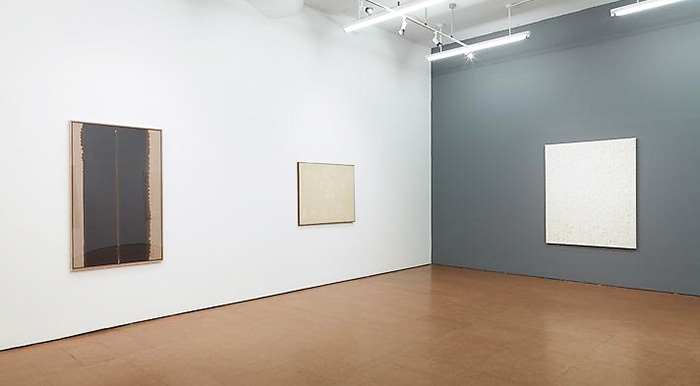

Overcoming the ModernDansaekhwa:The Korean Monochrome Movement, 2014, Alexander Gray Associates.

The first Korean monochrome painting exhibition in New York was the group exhibition “Overcoming the Modern Dansaekhwa: The Korean Monochrome Movement” (2/19/14-3/29/14) held at Alexander Gray Associates in Chelsea in 2014. This exhibition, which showed Lee Ufan, Park Seo-Bo, Yun Hyong-Keun, Chung Sang-Hwa, Ha Jong-Hyun, Hur Hwang, and Lee Dong-Youb, and was curated by Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath through research in Korea. Bardaouil and Fellrath were selected as curators for the 2021 La biennale de Lyon, France.

In September of the same year, LA’s Blum & Poe Gallery held a group exhibition of master Dansaekhwa artists, “From All Sides: Tansaekhwa on Abstraction” (9/13/14-11/8/14) was presented. The curator was Joan Kee, a professor at the University of Michigan, who authored “Contemporary Korean Art: Tansaekhwa and the Urgency of Method” (University of Minnesota Press), the first English-language book to establish Dansaekhwa as a theory in 2013.

Dansaekhwa and Minimalism , 2017, Blum & Poe

Blum & Poe Gallery later held a comparative exhibition of Korean and American monochrome paintings in LA and New York in 2016 titled “Dansaekhwa and Minimalism” (1/16/16-3/12/16-LA, 4/14/16-5/21/16-NY). The exhibition featured Korean monochrome painters such as Lee Ufan, Chung Sang-Hwa, Park Seo-Bo, Yun Hyong-Keun, Ha Chong-Hyun, and Kwon Young-Woo, as well as works by American artists Agnes Martin, Robert Ryman, Robert Irwin, Sol LeWitt, Richard Serra, Carl Andre, and others.

In October 2015, Christie’s New York held a group exhibition of Dansaekhwa masters, “Forming Nature: Dansaekhwa Korean Abstract Art.” This exhibition included Kim Whan-Ki (1913-1974), Rhee Seundja (1918-2009), Chung Chang Sup (1927-2011), and Yun Hyong-Keun (1927-2011), Park Seo-Bo (1931-2023), Chung Sang-Hwa (B. 1932), Ha Chong-Hyun (B. 1935), and Lee Ufan (B. 1936).

Forming Nature: Dansaekhwa Korean Abstract Art, 2015, Christie's New York. Photo: Sukie Park/NYCultureBeat

Subsequently, starting from the fall of that year, solo exhibitions by masters of Dansaekhwa were held at major galleries in New York. In Manhattan in 2015, artist Ha Chong-Hyun’s “Conjunction” (Tina Kim Gallery), Chung Chang Sup’s “Meditation” (Gallery Perrotin), and Yun Hyong-Keun’s solo exhibition (Blum & Poe) were held simultaneously.

Afterwards, monochrome paintings found their place in collections at various locations, including the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the Guggenheim Museum (New York/Abu Dhabi), the Art Institute of Chicago, the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington DC, and the Centre Pompidou. At the same time, the prices of monochrome paintings skyrocketed in the auction market.

#Dansaekhwa: Exploring Origins and Rediscovery

Monochrome: Painting in Black and White, National Gallery, UK, 2017

Much like how black-and-white photography often conveys a more potent message than color, painters from Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres to Pablo Picasso and Gerhard Richter have frequently delved into monochrome, eschewing color. In 2017, the National Gallery in London hosted “Monochrome: Painting in Black and White” (10/30/2017-2/18/2018), showcasing works by Rembrandt, Ingres, Picasso, Richter, and Olafur Eliasson. The Guggenheim Museum in New York also held an exhibition featuring Picasso’s black and white paintings (“Picasso Black and White,” 10/5/2012-1/23/2013) in 2012.

Agnes Martin Retrospective@Guggenheim Museum, 2016 Photo: Sukie Park/NYCultureBeat

From “Korean Monochrome Painting” to “Dansaekhwa,” the journey of Korean monochrome art, which evolved into its own ideology, incorporates elements of Minimalism seen in artists like Alexander Rodchenko, Kazimir Malevich, and Agnes Martin. It stands distinct from the Color Field Abstraction of artists such as Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko.

Korea: Five Artists, Five Hinsek ‘White,' Tokyo Gallery, 1975

Popular in Korea in the 1970s, Korean Dansaekhwa was a movement that risked fading into obscurity on the global stage. How did Dansaekhwa gain international recognition after four decades?

The genesis of monochrome painting can be traced back to the first Indépendant exhibition held at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gyeongbokgung Palace in 1972. The white paintings by Lee Dong-Youb (1946-2013) and Hur Hwang (1946- ) showcased in this exhibition were selected for the Paris Biennale (La Biennale Paris) by artist Lee Ufan, a jury member. The inaugural monochrome painting group exhibition, “Korea: Five Artists, Five Hinsek ‘White’,” took place at the Tokyo Gallery in Ginza, Tokyo, in 1975. Participating artists included Kwon Young-Woo (1926-2013), Park Seo-Bo (1931-2023), Seo Seung-Won (1941-), Heo Hwang, and Lee Dong-Yeop. For Korean artists, white symbolizes the spirituality of the Korean people, embodied by white clothing and Joseon white porcelain. As monochrome painting gained traction globally, the Tokyo Gallery revived an exhibition with the same title 43 years later, in 2018.

CHUNG SANG-HWA: Tansaekhwa, May 31, 2016, Dominique Lévy Gallery. Photo: Sukie Park/NYCultureBeat

“Working with Nature: Traditional Thought in Contemporary Art from Korea” (4/8-6/1/1992), a group exhibition featuring Chung Chang-Sup, Yun Hyong-Keun, Kim Tschang-yeul, Park Seo-Bo, Lee Ufan, and Lee Kang-So at the Tate Gallery Liverpool, UK, in 1992, showcased 71 works. These six artists, who were between the ages of 7 and 23 when the Korean War erupted, drew inspiration from nature, crafting dynamic, textured works. This predates the formal recognition of “Dansaekhwa.”

In 1995, the exhibition “Ecole de Seoul 20 Years - Monochrome 20 Years” was hosted at KwanHoon Gallery in Seoul, initially under the title “Monochrome” before the term “Dansaekhwa” gained prominence. The subsequent year, Gallery Hyundai presented “Korean Monochrome Painting in the 1970s,” featuring works by Chung Chang-Sup, Yun Hyong-Keun, Kim Tschang-yeul, Park Seo-Bo, Chung Sang-Hwa, Lee Ufan, Ha Jong-Hyun, Kim Guiline, Lee Seung-Jo, Seo Seung-Won, Choi Myeong-Young, Lee Dong-Youb, and Young-woo Kwon.

The term “Dansaekhwa” was initially used by the curator Jinseop Yoon to refer to modern Korean monochrome painting in the English catalog for the special exhibition “A Cross Section of Korean and Japanese Contemporary Art” at the 3rd Gwangju Biennale in 2000. This exhibition delved into the aesthetic qualities, stylistic characteristics, and production methods of Korean Dansaekhwa and Japanese Monoha, juxtaposing them with Western minimalism, Western object aesthetics, and Italy’s Arte Povera, respectively.

The “Korean Monochrome Painting” exhibition (3/17-5/13/2012) held at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Gwacheon in 2012, curated by Jinseop Yoon, marked the first official showcase of contemporary Korean monochrome painting. The exhibition featured over 150 works by 31 artists, including early Dansaekhwa pioneers like Kim Whan-Ki, Kwak In-sik, Park Seo-Bo, Lee Ufan, Yun Hyong-Keun, Chung Chang-Sup, Chung Sang-Hwa, and Ha Jong-Hyun, as well as later practitioners like Lee Kang-So, Moon Beom, Lee In-Hyeon, Kim Chun-Soo, and Noh Sang-Gyun.

In 2013, Joan Kee, a professor at the University of Michigan, published “Contemporary Korean Art: Dansaekhwa and the Urgency of Method,” marking the first study of monochrome painting outside of Korea. Hyun-Sook Lee, founder and chairwoman of Kukje Gallery in Seoul, showcased her monochrome paintings at the London art fair Frieze in May 2013, selling them to art collectors associated with prestigious museums like the Guggenheim in New York, the Dia Art Center, the Tate Gallery in London, and the Center Pompidou in Paris.

Dansaekhwa, May 8–August 15, 2015, Palazzo Contarini-Polignac , Photo: Kukje Gallery and Tina Kim Gallery/Ms. Hyun-Sook Lee & Ms. Tina Kim. Photo: Sukie Park/NYCultureBeat

In 2015, Korea’s Kukje Gallery (founder/ chairwoman Hyun-Sook Lee, as depicted above) and New York’s Tina Kim Gallery presented a special exhibition at the 56th Venice Biennale (La Biennale de Venezia) titled “Dansaekhwa” (5/18-8/15/2015), held at Palazzo Contarini-Polignac, which was curated by Lee Yong-Woo, the former artistic director of the 2004 Gwangju Biennale. Featuring works by Kim Whan-Ki, Kwon Young-Woo, Lee Ufan, Park Seo-Bo, Chung Chang-Sup, Chung Sang-Hwa, and Ha Jong-Hyun, the exhibition offered a unique perspective on Dansaekhwa’s aesthetics and historical significance, positioning it within the realm of global art history.

Dansaekhwa has now firmly established itself within the annals of world art history, joining the ranks of similar movements such as Japan’s Gutai art and Monoha, Italy’s Arte Povera, and Germany's ZERO group. It continues to evolve as a significant school of art in the global cultural landscape.

#1970s: Why was it monochrome?

Yun Hyong-Keun, January 17-March 7, 2020, David Zwirner, NYC Photo: Sukie Park/NYCultureBeat

In the 1970s, Korean workers, intellectuals, and artists resisted Park Chung Hee’s dictatorship in their own ways. Garment worker Jeon Tae-il committed suicide by setting himself along with a copy of the Labor Standards Act on fire at the age of 22 in 1970, and poet Kim Chi-ha was imprisoned for violating the anti-communism law in 1970 after publishing the poem “Five Jeoks,” which satirized government corruption and malfeasance. In 1971, singer Kim Min-ki released his debut album “Morning Dew,” and this song, which became a protest song, was banned by the Yushin Government’s Emergency Measure No. 9 in 1975.

Under the military regime, elite painters fell into monochrome. The first generation of monochrome artists, including Yun Hyong-Keun, Chung Sang-Hwa, Chung Chang-Sup, Park Seo-Bo, and Ha Chong-Hyun, resisted in silence in despair. For this reason, folk painters who participated in social movements in the 1980s after the Gwangju Uprising, criticized Dansaek painters as “ignoring reality,” “imitating Western minimalism,” and “lack of individuality.”

Marisol, Diptych(1971)/ John Outterbridge, Broken Dance(1978-82)/ 하종현(Ha Chong-Hyun), Conjunction 74-26(1974). #420, Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Sukie Park/NYCultureBeat

Was Dansaekhwa an escape from reality for them, or was it resistance?

The life of Yun Hyong-Keun, who was the son-in-law of Kim Whan-Ki, the “pioneer of Korean abstract painting,” was marred by resentment. In 1947, he participated in the anti-government movement as an art student at Seoul National University and was expelled. Immediately after the outbreak of the Korean War, he was dragged into an anti-communist organization due to his protests during his college years. In 1956, he served six months in Seodaemun Prison on the grounds that he did not flee during the war and served as a collaborator in Seoul.

In 1973, while working as an art teacher at Sookmyung Girls’ High School, he questioned the corruption of a student from a wealthy family who had been illegally admitted to school through the power of the head of the Central Intelligence Agency, and he was arrested on the grounds that he had violated the anti-communist law by wearing a “Lenin beret.” He began drawing in earnest in 1973 at the age of 45. Shocked by the massacre of citizens during the Gwangju Uprising in May 1980, he left for Paris with his family.

David Reed(1946, San Diego, California- ), #90, 1975, Oil on five joined canvases (left)/ Park Seo-Bo(1931, Yecheon, Korea - ), Ecriture No. 55-73, 1973, Graphite and oil on canvas. Guggenheim Museum Photo: Sukie Park/NYCultureBeat

Park Seo-Bo who passed away in 2023, once said that painting means cultivating the body and mind. “At one time, I received social scorn, asking, ‘Is that even a painting?’, but my work is the result of an act that I repeated endlessly, like a monk chanting a sutra repeatedly. A painting is a tool to empty oneself, and the residue from the process of receiving is a painting. It is not just a residue, but a crystallization of the spirit.”

In 2019, the Cranbrook Art Museum in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan held an exhibition “Landlord Colors: On Art, Economy, and Materiality” (6/21/19-10/6/19), including artists from Korea, Italy, Greece and Cuba, which introduced works created during a period of economic and social turbulence. The exhibition included Korean artists’ work created during the Yushin dictatorship in the 1970s, including painters Lee Ufan, Ha Chong-Hyun, Kwon Young-Woo, Park Hyun-Ki, Park Seo-Bo, and Yun Hyong-Keun.

#Color: The Spectrum of Freedom

Chung Chang-Sup, Meditation, 2015, Galerie Perrotin, New York

Under the military dictatorship of the 1970s, human rights were suppressed, and artists couldn’t enjoy creative freedom due to censorship. Painters may not have had the luxury of freely selecting a variety of colors from their palettes. Monochrome could be a metaphor for pure color that resists the oppression of the Yushin system, the severely authoritarian constitutional reform implemented during President Park Chung Hee’s Fourth Republic (1972-79).

Monochromatic painters embraced minimalism, opted for achromatic colors such as gray, brown or white, and used Korean media and techniques such as calligraphy, ink-and-wash painting, Korean paper, gunny cloth, kaolin, back pressure, and engraving. It is a repetitive work performed over a long period based on the tradition of ink-and-wash painting and the Lao-tzu philosophy of pursuing unity with nature. As a result, the two-dimensional canvas contains the flavor of Korean ingredients and unique textures, as well as the emotions of the Korean people, such as the pain, resentment, and oppression of an era. It is Korean abstract painting, a landscape of the mind, where time, density, and energy (ki) are clearly felt.

Artist Park Seo-Bo applies paint and then draws hatches with a pencil before it dries; artist Yun Hyong-Keun paints blue and brown paint repeatedly on cotton cloth or linen and spreads it; artist Chung Sang-Hwa repeatedly tears and fills in the canvas with layers of clay slip; artist Chung Chang-Sup, who kneads bamboo shoots from above; and artist Ha Jong-Hyun, who applies thick paint to the back of a gunny sack and pushes it out to the front, employed unique styles and methods as masters of monochrome painting.

Kim Guiline, Selected Works: 1967–2008, Lehmann Maupin, New York. Photo: Elisabeth Bernstein

Meanwhile, in 2017, Lehmann Maupin Gallery held the first American solo exhibition “Kim Guiline / Selected Works: 1967–2008” by artist Kim Guiline. Artist Kim, who moved to France in the 1960s, did not experience the Yushin regime of the 1970s. In the late 1960s, he worked on geometric abstractions using primary colors reminiscent of the five colors of red, yellow, blue, and green, but later evolved into monochrome paintings using these primary colors rather than use of 'achromatic colors of silence and resistance,' which distinguishes him from the Dansaekhwa Five.

Therefore, Korean Dansaekhwa is different from Western Minimalism or Monochrome Painting. Unlike Minimalism, which focuses on the artist’s conceptual expression, Dansaekhwa works imply the ascetic and meditative energy of Korean painters during the period of political oppression. It is an ‘invisible painting of the mind,’ completed by emptying the mind with a spirit of resistance and completing labor-intensive repetitive actions. It is a painting that appears empty like a moon jar but feels full of heart and texture.

#DANSAEKHWA Genre Authorized

The New York Times has also taken note of monochrome painters. A June 2021 article, “A Towering Figure in South Korean Art Plans His Legacy,” featured the life and work of artist Park Seo-Bo, a key figure in the Dansaekhwa movement. In April 2022, the New York Times published a review of the Venice Biennale exhibition (Postcards from the Biennale: His paintings travel, but Ha Chong-Hyun stays in Korea; Anselm Kiefer melds art and sculpture at the Doges Palace), featuring artist Ha Chong-Hyun and German master Anselm Keifer’s exhibition side by side.

Korean monochrome painting, discovered belatedly, is now recognized as a genre in art history. The Tate art museum in London explains monochrome painting as an art term and formal art genre as follows on its website.

DANSAEKHWA: THE KOREAN MONOCHROME MOVEMENT

“Stylistically the artists of Dansaekhwa rejected realism and formalism for modernist abstraction, choosing to paint only in monochrome and in a style that emphasised the flatness of the canvas. The movement highlighted the post-war struggle within Korea over national identity, belonging and tradition. By using repetitive patterns and gestures in their pictures they attempted to create an aesthetic style that was universal and belonged to no one.”

#Special exhibitions of Non-Dansaekhwa Korean art at American art museums

Apart from Dansaekhwa, K-art exhibitions are being held one after another at major art museums in the United States. The Metropolitan Museum of Art held a large-scale exhibition “Silla (57 BCE – 935 CE): Korea’s Golden Kingdom” from November 2014 to February of the following year. In this exhibition, about 100 pieces of Silla art were introduced, including national treasures such as the Hwangnamdae Chongbuk Monument, the Gyeongju Old Hwang Dong-gil Seated Buddha, the pottery equestrian figure-shaped inscription, and the clay decoration cabinet. Subsequently, the Philadelphia Museum of Art launched “Art of the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910): Treasures from the National Museum of Korea” in March 2015, which exhibit traveled to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Houston Museum of Art in Texas.

After these major art museums introduced Silla and Joseon art, special exhibitions looking at modern and contemporary Korean art began to be held along with the Dansaekhwa craze. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) opened the solo exhibition “Park Dae Sung (1945- ): Virtuous and Contemporary Brush” by ink painting master Park in July 2022, and from September of that year to February of the following year, the same museum exhibited “The Space Between: The Modern in Korean Art,” which explored the evolution of Korean art from 1897 to 1965. The exhibition showcased about 130 works by 88 artists, including Kim Whan-Ki, Lee Jung-seob, Park Soo Keun, Rha Hye-sok, Lee Ungno, Yoo Youngkuk, John Pai, Shin Nakkyun, Quac Insik, Ko Hui-dong, and Lee Qoede.

Meanwhile, New York’s Guggenheim Museum exhibited “Experimental Art in South Korea, 1960s-70s” from September 2023 to January 2024. This exhibition showcased works by Lee Kang-So, Lee Kun-Yong, Seung-taek Lee, Kim Kulim, Sung Neung Kyung, Jung Kangja and others. And, the Philadelphia Museum of Art held a special exhibition of Korean contemporary art, “The Shape of Time: Korean Art After 1989,” from October 2023 to February 2024, featuring Do Ho Suh and Byron Kim, Suntag Noh, Kyungah Ham, Meekyoung Shin, Michael Joo, Yeondoo Jung, and Suki Seokyeong Kang among works from 33 artists.

In addition, the San Diego Museum of Art held “Korea in Color: A Legacy of Auspicious Images” from October 2023 to March 2024, the Metropolitan Museum of Art has an exhibition “Lineages: Korean Art at the Met” from November 2023 to October 2024, and the Denver Museum is showcasing “Perfectly Imperfect: Korean Buncheong Ceramics” for two years starting from December 2023.

In 2021, Min Jung Kim was appointed as the first female director of the St. Louis Museum of Art in its 142-year history. Director Kim is also the first Korean director of a major U.S. art museum. Now, most major art museums in the U.S. have curators dedicated to Korean art. Curator Soyoung Lee, who had worked at the Metropolitan Museum of Art beginning in 2003, was selected as chief curator of the Harvard Art Museum in 2018. Then, the Met recruited Eleanor Soo-ah Hyun, who was the curator of the British Museum in London. At the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Curator Hyunsoo Woo has overseen Korean art since 2006 and also serves as the head of the East Asian Art Department. In addition, Virginia Moon has been working in the Korean Art Department at the LA County Museum of Art since 2013, Sooa Im McCormick has been working in the Korean Art Department at the Cleveland Museum of Art since 2015, and Kyung An has been working in the Asian Art Department at the Guggenheim Museum since 2015. And San Francisco MOMA appointed Eungie Joo, sculptor Michael Joo's sister, as the Museum’s First Curator of Contemporary Art in 2017. Meanwhile, President Lee Boo-jin of Hotel Shilla in Korea was elected as one of LACMA's 11 new board members in March 2023.

#K-ART: Seoul Emerges as a Global Art Mecca

The roots of K-Art and K-Movies can be traced back to the mid-1990s, notably with the Gwangju Biennale and Busan International Film Festival, predating the rise of K-pop and K-drama in the Korean Wave. The Gwangju Biennale, established in 1995, and the Busan International Film Festival, inaugurated in 1996, played pivotal roles in shaping Korea’s cultural landscape.

The Gwangju Biennale, situated in Gwangju, Jeollanam-do, a city rich in cultural history and known for the May 18 Uprising, has solidified its position as the oldest and most prestigious biennale in Asia. In 2014, Artnet.com, an online art media platform, ranked it among the world’s top five festivals, alongside Italy’s La Biennale di Venezia, Germany’s Documenta in Kassel, New York’s Whitney Biennial, and the pan-European Manifesta biennial.

And now thanks to the rise of Dansaekhwa and the Korean Wave, Seoul has positioned itself as a prominent destination on the world art map. As the Korean art market gains momentum, galleries from New York and Europe are establishing branches in Seoul one after another. In 2016, the Paris-based Gallery Perrotin became the first global gallery to open a Seoul branch in Samcheong-dong. Having previously hosted a solo exhibition of monochrome painter Chung Chang-Sup in New York in 2014, Perrotin expanded its presence with Perrotin Dosan Park in Sinsa-dong in 2022.

In October, Barakat Contemporary, known for its operations in London, Abu Dhabi, and LA, opened its first Asian branch in Samcheong-dong. In March 2017, New York’s influential Pace Gallery, which represents artist Lee Ufan, launched a Seoul branch in Hannam-dong. Also in 2017, New York’s Lehmann Maupin, representing artists Bul Lee and Do Ho Suh, inaugurated a Seoul branch. KönigGalerie in Berlin, selling Koo Jeong A’s works, opened a gallery in Apgujeong-ro in 2021. Additionally, Austrian Thaddaeus Ropac, opened a gallery in Hannam-dong. In April 2022, New York’s Gladstone Gallery, home to artists like Anicka Yi and Matthew Barney, opened its first branch in Asia in Cheongdam-dong.

A major art fair has also made its way to Seoul. In September 2022, the international art fair Frieze was held in Seoul for the first time. Frieze, previously hosted in New York, LA, and London, arrived in Seoul as its first Asian city. Hyun-Sook Lee, founder/chairwoman of Kukje Gallery, first introduced Dansaekhwa at Frieze London in 2013. Frieze Seoul took place simultaneously with KIAF Seoul, at the COEX building in Seoul.

The inaugural Frieze Seoul featured 119 galleries from 20 countries worldwide, including Hauser & Wirth, Gagosian, Lehmann Maupin, Perrotin, Kukje, Hyundai, Arario, PKM, Leeahn Gallery, Jason Ham, Johyun Gallery, and Hakgojae Gallery, alongside KIAF Seoul, with a total of 164 galleries from 17 countries. Furthermore, KIAF Plus, involving 73 galleries, was newly established, gathering over 350 galleries and solidifying Seoul’s status as an emerging art city representing Asia.

K-Art has created a synergistic impact alongside K-Pop and K-drama. Artnet.com reported on the substantial presence of Korean celebrities during the inaugural Frieze Seoul. In the article titled “Korean Celebrities Showed Up in Full Force for Frieze Seoul—and Some of Them Actually Came to Look at the Art,” Artnet highlighted the extensive attendance of top Korean celebrities, ranging from K-pop singers to Netflix streaming stars and Oscar-winners. The launch celebration party, hosted by CJ Group at the Leeum Museum of Art, showcased prominent figures, including Squid Game stars Lee Jung-jae and Lee Byung-hun, actors Song Seung-heon, Cha Seung-won, and Youn Yuh-jung, the Oscar-winning supporting actress. The event also featured BTS’s RM and J-Hope, Psy, the nine-member girl group Kep1er, hip-hop duo Dynamic Duo, and more. The week marked a significant turnout for the debut of the international art fair, showcasing not only global talents but also homegrown artistic prowess as Seoul aims to establish itself as the leading art hub in Asia.

Sukie Park

A native Korean, Sukie Park studied journalism and film & theater in Seoul. She worked as a reporter with several Korean pop, cinema, photography and video magazines, as a writer at Korean radio (KBS-2FM 영화음악실) and television (MBC-TV 출발 비디오 여행) stations, and as a copywriter at a video company(대우 비디오). Since she moved to New York City, Sukie covered culture and travel for The Korea Daily of New York(뉴욕중앙일보) as a journalist. In 2012 she founded www.NYCultureBeat.com, a Korean language website about cultural events, food, wine, shopping, sightseeing, travel and people. She is also the author of the book recently-published in Korea, "한류를 이해하는 33가지 코드: 방탄소년단(BTS), '기생충' 그리고 '오징어 게임'을 넘어서 (33 Keys to Decoding the Korean Wave: Beyond BTS, Parasite, and Squid Game)."

정창섭 화백은 내가 고교시절(이화여고)에 예고 미술 선생이셨습니다. 키도 크고 잘 생기셔서 인기가 많았습니다. 예고와 같이 한 건물을 썼기 때문에 정창섭 선생님은 매일 볼 수 있었고, 선생님의 그림도 방과 후나 노는 시간에 올라가서 보곤 했습니다. 우리 교실 바로 위층이(맨 꼭대기층) 미술 작업실이 었으니까요. 그림이 크고 단색화가 아니고 색채가 있었던 걸로 기억되는데? 매일 선생님을 봤고, 그림을 봤습니다.

이성자씨는 파리에서 미술을 공부하고 와서 60년대에 전시회를 열었는데(서울 어딘데 장소 이름은 섕각안남) 감명 깊게 봤지요. 파리에서 공부하고 오셨다고 해서 멋진 파리쟌으로 생각하고서 친구랑 같이 갔었죠. 그런데 너무 수수하고 파리의 체취는 전혀 없어서 친구랑 이성자 화백 흉을 본 기억이 나네요. 게다가 그 당시 위키 리란 개그맨이 있었는데 이성자 화백의 남동생이라고 해서 친구랑 화랑 구석퉁이에서 낄낄 웃은 기억이 납니다.

세월이 쏜 화살처럼 지나갔습니다. 초로의 노인이 돼서 그때를 생각하면서 행복한 미소를 짓습니다. 컬빗 덕에 이런 추억을 꺼내게됨을 감사드립니다. 오늘은 엔돌핀을 많이 갖게돼서 신이 납니다.

나의 사랑 뉴욕컬빗아, 잘 있어요.

-Elaine-