Old Masters

2019.06.23 17:01

크리스티 밀반출 가능 투탕카멘 조각상 600만 달러에 팔려

조회 수 1900 댓글 0

이집트, 밀반출 투탕카멘 경매 중단 촉구

1905년 카르나크 신전 발굴 후 독일인 소장

*이집트가 경매 중단을 요청했던 투탕카멘 조각상이 크리스티 런던에서 600만 달러(470만 파운드)에 팔렸다. 예상가는 500만 달러였다. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-48865336

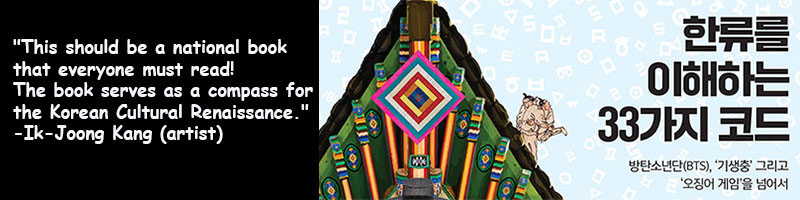

크리스티 경매에 나온 투탕카멘 석상(왼쪽). 1922년 발굴된 투탕카멘의 황금 마스크. Photo: Roland Unger/Wikipedia

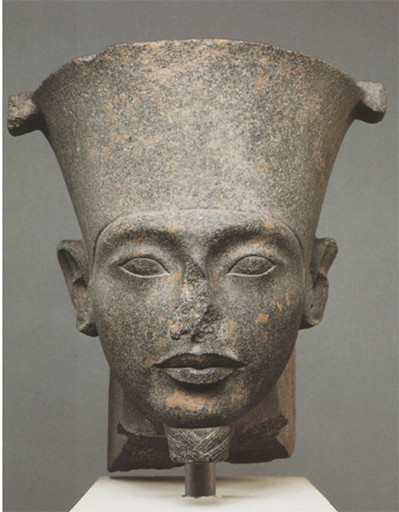

크리스티 런던이 오는 7월 4일 투탕카멘(Tutankhamun, King Tut) 조각상을 경매한다. 예상가는 400만 파운드(약 500만 달러, 약 59억원). 하지만, 이집트 정부는 밀반출 가능성이 있다며 경매를 중단하고, 조각상을 반환하라고 요구했다. 투탕카멘 두상은 고대 이집트 신왕국 18왕조의 파라오, '소년왕' 투탕카멘의 머리에 신 아문(Amun, Amen)의 형상을 하고 있다. 소재는 갈색 규암이며, 크기는 11 1/4인치(28.5cm).

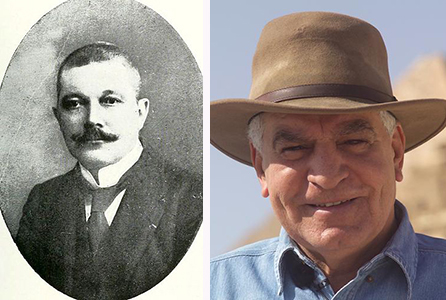

이집트 정부는 크리스티 런던에 투탕카멘 조각상 및 함께 경매될 이집트 유물의 판매를 중단하라고 촉구했다. 이집트의 고대유물위원회 최고위원장을 지낸 고고학자 자히 하와스(Zahi Hawass) 박사는 "크리스티가 이 조각상이 합법적으로 이집트를 떠났는지를 증빙할 서류가 없다고 생각한다. 그것은 불가능하다"고 밝혔다. 이집트 전문 고고학자들은 투탕카멘 조각상이 룩소르의 카르나크 신전에서 출토된 조각상과 유사점이 많은 것으로 보아 불법적인 경로로 반출된 것으로 확신하고 있다.

이집트 신왕국 19왕조(약 1292-1185BC) 왕족 두상(6만8750파운드)/ 19-20왕조(약 1250-1150BC) 파라오 아멘호텝과 왕비 아흐메스-네페르타리 석상(3만7500파운드), 18-19왕조(약 1319-1213 BC) 왕족 두상(18만 3천파운드) The Resandro Collection, London Christies, 2016년 12월.

한편, 크리스티는 조각상의 소유 경로(프로비넌스, Provenance)는 1985년 투탕카멘 조각상은 1960년대까지 빌헬름 폰 투른앤 탁시스 왕자 소장품이었으며, 1973년경 비엔나의 아트딜러 조셉 메시나가 구입한 후 1982년 아놀프 로슈만에게 팔렸으며, 1985년 뮌헨의 하인츠 헤르체르가 구입했으며, 1985년부터 레산드로 컬렉션(The Resandro collection)이었다. 그리고, 크리스티는 2016년 레산드로 컬렉션 세일에서 300만 파운드(약 400만 달러) 이상의 판매고를 올렸다.

투탕카멘 조각상은 1905년 카르낙에서 프랑스 고고학자 조르쥬 르그랭(George Legrain, 1865-1917)이 발굴했다고 크리스티는 밝히고 있다. 조르쥬 르그랭은 1903년 카르나크의 아문 사원(Temple of Amun)에서 발굴작업을 시작했으며, 1907년까지 800여점의 석상이 나왔다. 르그랭은 제 1차 세계대전 발발 후에도 룩소르에 남아 발굴 작업을 사진 1200여점으로 남겼으며, 1917년 갑자기 사망했다.

프랑스 고고학자 조르쥬 르그랭(왼쪽), 이집트 고고학자 자히 하와스 박사

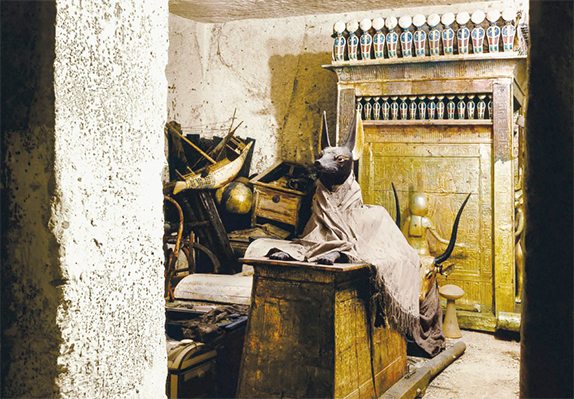

'소년 왕' 투탕카멘(약 1341-약 1323 BC)의 본명은 투탕카텐(Tutankhaten)으로 파라오 아케나텐(Akhenaten)과 그의 첩 키야(Kiya) 사이의 아들로 9세에 파라오에 즉위했다. 계모인 네페르티티(Nefertiti)의 딸과 결혼했으며, 즉위 3년 후엔 이름을 투탕카멘으로 바꾸면서 아버지 아케나텐이 숭배하던 유일신인 태양원반 아텐교(Aten)을 배척하고, 이전의 아문교(Amun)로 복귀했으며, 18세에 갑자기 요절했다. 1922년 나일강 서쪽 왕들의 계곡(Valley of the Kings)에서 영국의 고고학자 하워드 카터가 이끄는 발굴팀이 투탕카멘 묘를 발굴해 황금가면을 비롯, 5,398점의 유물이 나와 세계적으로 센세이션을 일으켰다.

1970년 유네스코(UNESCO) 협약은 문화유산의 불법거래를 방지하기 위해 뮤지엄들이 이전에 수출된 것으로 입증되지 않은 유물은 구입하지 않고 있다. 한편, 이집트 정부는 1983년 이전에 발굴된 유물이 법적 소유권을 증명할 수 없거나 이후 발굴된 유물은 모두 국가 재산으로 이를 거래하거나 수출을 금지하는 법을 제정했다.

Christie's press release

AN EGYPTIAN BROWN QUARTZITE HEAD OF THE GOD AMEN WITH THE FEATURES OF THE PHARAOH TUTANKHAMEN

NEW KINGDOM, 18TH DYNASTY, REIGN OF TUTANKHAMEN, CIRCA 1333-1323 B.C.

A remarkable representation of the young king as the god Amen, recognizable by the distinctive crown with flaring sides and slightly convex top, once surmounted by tall double feathers with details carved in relief, the superbly modelled facial features with a deep depression between the naturalistic eyes and eyebrows, sensitively carved, the fleshy face with high cheekbones, the mouth particularly sensual with thicker upper lip and small full lower lip in a faint smile with downturned corners, the eyes and mouth with well defined contour lines, the ears left visible and elegantly framed by the sides of the crown, the rounded chin and false beard now missing, the head probably part of a seated statue originally, with support present at the back

11 ¼ in. (28.5 cm.) high

Provenance

Understood to have been in the collection of Prinz Wilhelm von Thurn und Taxis (1919-2004) by the 1960s.

with Josef Messina, Galerie Kokorian & Co, Vienna, acquired from the above in 1973 or 1974.

with Arnulf Rohsmann, Klagenfurt, acquired from the above in 1982 or 1983.

with Heinz Herzer, Munich, acquired from the above in June 1985.

The Resandro collection, Germany, acquired from the above in July 1985.

Literature

S. Schoske and D. Wildung, Konzeption der Ausstellung und Katalog Heinz Herzer, Ägyptische und moderne Skulptur Aufbruch und Dauer, 1986, pp.126-130, no. 56.

M. Pfaffinger, Die Amonstatuen der Nachamarnazeit, Master thesis (unpublished), Munich, 1987, cat. no. 16.

S. Schoske and D. Wildung, Gott und Götter im alten Ägypten, Mainz, 1992, pp. 22-25, no. 11.

D. Wildung, 'Gott und Götter im alten Ägypten,' in Antike Welt, Vol. 23, no. 3, 1992, pp.198-199.

A.-C. Thiem (ed.), Am Hofe des Pharao. Von Amenophis I. bis Tutanchamun. Palais del Arte, Bussolengo, 2002, p. 105, fig. 111.

J. Malek, D. Magee and E. Miles, Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Statues, Reliefs and Paintings, Volume VIII, Parts 1 and 2: Objects of Provenance Not Known: Statues, Oxford, 2008, no. 802-049-650.

I. Grimm-Stadelmann (ed.), Aesthetic Glimpses, Masterpieces of Ancient Egyptian Art, the Resandro Collection, Munich, 2012, p. 41, no. R-134.

Exhibited

Berlin, Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung; Berlin, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin; Munich, Staatliche Sammlung Ägyptischer Kunst Munchen; Hamburg, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg, Gott und Götter im Alten Ägypten, 1992-1993.

Palma de Majorca, Palacio del Arte, Am Hofe des Pharao: von Amenophis I. bis Tutanchamun, 4 May-27 October 2002.

Lot Essay

THE REIGN OF THE BOY-KING AND THE RESTORATION

The origin, royal accession and death of Tutankhamen are, to this day, very disputed among specialists. Recent archaeological and scientific discoveries have shed new light, sometimes adding more hypothesis than consensus on these aspects.

Born in Tell elAmarna, and then known as Tutankhaten, he was most probably the son of Akhenaten. A limestone block found in Hermopolis and dating from the reign of Akhenaten contains a hieroglyphic text describing him as ‘King’s son of [his] body whom he loves, Tutankhuaten’ (M. Eaton-Krauss, The Unknown Tutankhamun, London, 2016, p. 3), But the question remains if he was born of Nefertiti, or his secondary wife Kiya. Although often criticised, DNA analysis made in the last decade have proposed that Tutankhamen was the son of the man whose remains lay in the coffin found in the tomb KV55 (op. cit., p. 7), thought to be Akhenaten. His mother is absent from any noteworthy record, and it seems likely that she had died before his accession (op. cit., p. 11).

Nearly all specialists agree that a woman briefly occupied the throne after the death of Akhenaten: Ankhetkheperure, beloved of Akhenaten, Neferneferuaten. That she was in fact Nefertiti, or her daughter Meritaten, is still open for debate. It is believed that Tutankhaten was only 9 years old when he acceded the throne. A crook and a flail found in his tomb (object no. 269f and 44u respectively) are child-size (op. cit. p. 18). During the reign of his father Akhenaten, the focus turned towards a single god, the Aten or sun-disk, and the worship of any other was abandoned, making him the first monotheistic king in history.

But as soon as he passed away, the rehabilitation of the cult of Amen and the other traditional deities started. It had therefore begun even before the accession of Tutankhaten to the throne, but his reign saw the completion of a formidable number of projects (op. cit., p. 33), and to reinforce the return of the orthodoxy, the king changed his name to Tutankhamen in year 3 of his reign. An important monument from this period, made of quartzite, was found by George Legrain in 1905 at Karnak, The Restoration Stela, which irrevocably signalled the end of the Amarna period on a political and religious level. The art from Amarna on the contrary would continue to live through the artists and workshops who had moved to Thebes and fashioned the sculptures of the restoration program.

END OF A DYNASTY AND DISCOVERY OF THE CENTURY

The speculations regarding how Tutankhamen died are numerous, some grounded on scientific analysis, some from interpretation of archaeological remains: chariot accident, broken leg followed by infection, congenital diseases, assassination. It is understood that he died young, in the 9th year of his reign, probably at the age of 18, and that he died unexpectedly and abruptly. His widow, Ankhesenamen then sent a letter to the King of the Hittites, the powerful and sometimes menacing kingdom from Anatolia, asking him to send his son to become the King of Egypt. She was afraid and, probably with Horemheb in mind, writes that she would not take one of her own servants as husband. But the Hittite prince died on his way to Egypt (if not murdered), and never stepped foot in the Nile Valley (cf. E. Freed (ed.), Pharaohs of the Sun, Boston, 1999, p. 183).

As the 18th was coming to an end, Ay, the Vizir of Tutankhamen, now an old man, married Ankhesenamen, and reigned for four years only. Horemheb, the almighty General of the Armies, emerged and claimed the crown to become the last Pharaoh of the 18th dynasty. His reign (1319-1292 B.C.) bridges the end of the chaos of the Amarna Period and the rise of the ambitious 19th Dynasty.

The discovery in 1922 by Howard Carter and the Earl of Carnavon of the nearly intact tomb of Tutankhamen was a worldwide event, and sparked a renewed interest in ancient Egypt. The location of the tomb had been lost already in antiquity, probably buried under stones coming from subsequent tomb building. At the end of the 20th Dynasty, burials were systematically dismantled but Tutankhamen’s tomb was overlooked: paradoxically, being forgotten allowed for the greatest discovery of the 20th century.

It took 10 years for Howard Carter to excavate, conserve and record the 5,398 objects found. According to Nicholas Reeves, 80% of the funerary equipment originated from the female pharaoh Neferneferuaten, including the famous gold mask, originally engraved for ‘the Beloved of Akhenaten’, possibly his wife Nefertiti.

ART : A LIVING IMAGE OF THE KING – THE AMARNA ARTISTIC LEGACY

One of the aspects of the restoration program was the creation of well over fifty sculptures of Amen, dated by an inscription, or datable based on the iconography and style of the post-Amarna period (M. Eaton- Krauss, op. cit., p. 53), and which the present lot is part of. Amen’s iconography comprises his peculiar crown, which covers his head from his forehead to the nape of his neck, leaving the ears exposed; shaped like a truncated cone, its circumference increasing towards the top, which is slightly domed, and topped by a pair of tall falcon feathers. Four sculptures, either standing or seated, show the god with child-like physiognomy and were most probably made during the early years of his reign, see the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, acc. no.50.6, for an example in fine limestone, and the Ny Carlsberg Glyptothek, Copenhagen for another in granodiorite, inv. no. AEIN 1285. Statues depicting Amen alone were numerous, and so were statues showing the god together with the king.

First and foremost, it is the style of the face that blurs the border between an idealized representation of a god, and a royal portrait. The idea of using the king’s likeness on the representation of a worshipped deity was part of the traditional propaganda used by the ruler: to be shown in the guise of the powerful deity, with all the signs of divine power, which would therefore by attributed to him in his earthly reign (S. Schoske and D. Wildung, Gott und Götter im Alten Ägypten, Mainz, 1992, p. 24).

In Thebes, Tutankhamen and his successors Ay and Horemheb erected numerous statues of Amen. But establishing a precise date for them remains difficult as Horemheb obliterated all traces of Akhenaten and anyone connected to him in his Damnatio Memoriae campaign, and substituted his name on many of his predecessor’s statues. The features of the present lot are reminiscent of Amen statues in the temples of Luxor and Karnak, subsequently usurped by Horemheb, but dating from the time of Tutankhamen (S. Schoske and D. Wildung, ibid.).

As with most Egyptian stone sculptures, there is a slight asymmetry in this head: the left half of the face is fuller and more idealised than the right, and the right eye is larger than the left. (S. Schoske and D. Wildung, ibid.). Amen statues made during the reign of Tutankhamen such as our head show traits most closely identified with the Amarna style: soft, fleshy face with high cheek bones, sfumato eyes, and full lips reminiscent of Akhenaten in particular (cf. E. Freed (ed.), Pharaohs of the Sun, Boston, 1999, p. 188). It is ironic that the successors of Akhenaten, in trying to eradicate his ‘heresy’, carried on the naturalistic style engendered during his reign, and most evocative of his revolutionary vision.

It is worth mentioning two comparable works: a head of Amen in diorite (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 07.228.34, illustrated above) presenting a similar deep depression between the carved eyebrows and the slanted eyes which, together with the full mouth and downturned corners of the mouth are the features of Tutankhamen; and a seated statue of Amen in diorite protecting the king in the Louvre (inv. no. E 11609) which, although usurped by Horemheb, still bears two cartouches of Tutankhamen (R. Freed, op. cit., cat. nos 245 and 243 respectively).

틴토레토(Tintoretto) 탄생 500주년 북미 최초 회고전@내셔널갤러...

틴토레토(Tintoretto) 탄생 500주년 북미 최초 회고전@내셔널갤러...