CulBeat Express

2017.11.02 23:43

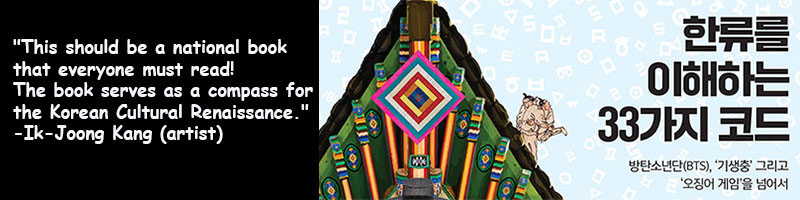

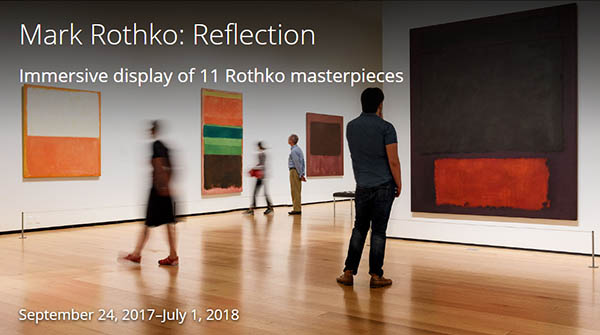

보스턴미술관 마크 로스코 특별전 'Reflection'(9/24-7/1, 2018)

조회 수 1124 댓글 0

Immersive Display of 11 Mark Rothko Paintings on View

at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Major Loans from National Gallery of Art, Washington, Make New England Debut

BOSTON (September 8, 2017)—In a career that spanned five decades, Mark Rothko (1903–1970) created some of the 20th century’s most evocative and iconic masterpieces. “A painting is not a picture of an experience,” he once remarked; “it is an experience.” This fall, 11 major works by the artist travel to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA), from the National Gallery of Art, Washington, for an immersive exhibition that invites visitors to become enveloped by Rothko’s large-scale paintings and encounter them as he had originally intended—to experience something more intimate and awe-inspiring than simply viewing.

Mark Rothko: Reflection, on view from September 24, 2017 through July 1, 2018, is the first focused display of the artist’s works at the MFA, showcasing the full sweep of his career—from early surrealist compositions; to the luminous, colorful canvases of his maturity; to the large, enigmatic “black paintings” made late in his life. Together, they trace the development of Rothko’s singular artistic vision and his quest to create works that produce emotional, even spiritual, responses. Additionally, the exhibition features a juxtaposition of Thru the Window (1938–39), an early Rothko painting on public view in the U.S. for the first time, and Artist in his Studio (about 1628), a masterpiece by Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn (1606–1669) from the MFA’s collection—both portraits of artists reflecting on the act of painting. Contrary to notions that Rothko’s works represented a dramatic break from the past, the side-by-side comparison underscores the modern artist’s view of his own paintings as part of a much longer tradition, rooted in his deep appreciation for the Old Masters. Mark Rothko: Reflection is on view in the John F. Cogan, Jr. and Mary L. Cornille Gallery. Presented with generous support from the Robert and Jane Burke Fund for Exhibitions. Additional support provided by an anonymous foundation and The Bruce and Laura Monrad Fund for Exhibitions.

“We’re grateful to our colleagues at the National Gallery of Art for their continued partnership, which has resulted in collaborations on many exhibitions over the years and now enables us to offer such a comprehensive presentation of Mark Rothko’s artistic vision,” said Elliot Bostwick Davis, John Moors Cabot Chair, Art of the Americas, who organized the exhibition. “Rothko’s paintings reward slow looking, and we invite MFA visitors to take their time and explore their own ways of experiencing his work.”

Rothko was born in 1903 in the Pale of Settlement, a territory of Russia in which Jews were allowed to reside permanently. By 1913, his family had immigrated to the U.S., settling in Portland, Oregon. After two years of study at Yale University, Rothko moved to New York in 1923 and began attending classes at the Art Students League. He quickly immersed himself in the city’s progressive artistic community, counting as friends and colleagues the painters Adolph Gottlieb, Robert Motherwell, Clyfford Still, Jackson Pollock and many others.

Rothko’s earliest works included cityscapes, landscapes, nudes and portraits. In Thru the Window (1938–39), he places himself—identified by his high forehead and thick, curly hair—on the threshold of a window facing the viewer, one hand resting on the ledge. He gazes onto an architectural space containing two symbols of his trade: a clothed model to his right and a bright red easel and canvas to his left. The position of the easel and canvas on the right side of the composition, as well as its visual prominence in the painting, recalls Rembrandt’s Artist in his Studio (about 1628). The small masterpiece depicts a painter—perhaps Rembrandt himself—confronting the daunting moment of conception and decision, an experience faced by artists of all generations. Rothko often turned to the Old Masters, particularly Rembrandt, for inspiration, and both artists used subjects of everyday life to evoke larger truths about the human experience. In Thru the Window and Artist in his Studio, a complex spatial strategy evokes the physical and intellectual distance between the artist and the tools of artistic creation.

Against the backdrop of the violence and anxiety of World War II, Rothko turned away from representational subjects in favor of more surreal and symbolic forms. Concerned about rising anti-Semitism, he also altered his name: from Marcus Rothkowitz to Mark Rothko. As the 1940s progressed, he experimented more and more with painting’s formal elements—color, shape, composition and depth—while shifting away from representation. During this time, Rothko came to believe that abstraction would further his aesthetic vision and facilitate the powerful, emotional response he sought. “It was with the utmost reluctance that I found the figure could not serve my purposes,” he later observed. Untitled (1945) is an example from this period, presenting an early, experimental use of horizontal bands of color that would come to define Rothko’s later works.

Between 1947 and 1949, Rothko began suspending colored forms with hazy outlines and dripping edges across his canvases. The exhibition includes No. 9 (1948) and No. 10 (1949), two examples from this small, transitional group of paintings that later became known as Rothko’s “multiforms,” to distinguish them from earlier, surrealist compositions and later, mature works. In the years following World War II, he ceased giving descriptive or narrative titles to his paintings, believing that they hindered the works’ potential transcendent qualities. “Silence is so accurate,” he once commented. Instead, nearly every canvas would be numbered, named after its palette of colors or remain untitled.

By 1950, Rothko’s compositions had settled into a recognizable format: large, rectangular, canvases; solid, applied grounds; and rectangular fields of color, often thinly applied and appearing to float at the painting’s surface. Refining and developing this formula, Rothko created an extensive body of so-called “classic” paintings. The exhibition presents four examples from this phase—Untitled (1949), Untitled (1955), Mulberry and Brown (1958) and No. 1 (1961). While these works may evoke a range of feelings and moods, Rothko rarely explained their meanings—he believed that the canvases, not the artist, should dictate a viewer’s sensory and emotional experience.

In 1964, Rothko completed more than a dozen “black paintings.” At first glance, these austere canvases may appear to be solid black—but with sustained looking, shapes emerge. Rothko created them as he did his classic, colorful canvases: by building up thin layers of paint, creating texture, depth—and even luminosity, despite the dark palette. This group of paintings includes No. 6 (1964), in which a single square floats to the surface, barely distinguishable from the black background. Additional “black paintings” on view in the exhibition include No. 7 (1964) and No. 8 (1964), which was recently conserved by the National Gallery of Art to display the nuances of Rothko’s aesthetic vision and is now seen by the public for the first time since treatment. Together, these works anticipate one of Rothko’s signature achievements—the Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas, founded by John and Dominique de Menil. Conceived from the start as a fully immersive experience of his paintings, plans for the nondenominational chapel consumed Rothko from 1964 to 1967. Eventually, he created 14 darkly painted canvases, which would be installed, surrounding the viewer, to create an enveloping, deeply meditative experience. Rothko did not live to see the chapel finished—physically ill and suffering from depression, the artist committed suicide in 1970.