CulBeat Express

2017.08.07 17:10

MoMA 루이스 부르주아 판화전(9.24-1/28, 2018)

조회 수 2232 댓글 0

MoMA EXPLORES LOUISE BOURGEOIS’S PRINTS AND BOOKS, A LITTLE KNOWN

YET INTEGRAL COMPONENT OF HER PRACTICE

With Some 300 Works, the Survey Sheds New Light on Bourgeois’s Creative Process and

Places Her Prints and Illustrated Books in the Context of Related Sculptures, Drawings,

and Paintings

Louise Bourgeois: An Unfolding Portrait

September 24, 2017-January 28, 2018

Floor Three, The Edward Steichen Galleries, and Floor Two, The Donald B. and Catherine C.

Marron Atrium

NEW YORK, August 7, 2017?The Museum of Modern Art’s Louise Bourgeois: An Unfolding

Portrait, on view September 24, 2017, through January 28, 2018, is the first comprehensive

survey of Bourgeois’s prints and illustrated books. It places these mediums within the context

of the artist’s overall practice and sheds new light on her creative process. The exhibition

includes 265 prints (including those in books and series), 23 sculptures, nine drawings, and

two early paintings. Louise Bourgeois is organized by Deborah Wye, Chief Curator Emerita of

the former Department of Prints and Illustrated Books?a longtime friend of the artist's and a

leading scholar of her work?with Sewon Kang, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Drawings

and Prints.

Louise Bourgeois (1911?2010), a celebrated sculptor who worked in multiple mediums, was

motivated by emotional struggle. Through art, she made her emotions tangible and sought to

understand and cope with painful memories, jealousy, anger, anxiety, loneliness, and despair.

Art was her tool of “survival,” she said, and her “guarantee of sanity.” This exhibition highlights

the themes and motifs that served as visual metaphors for Bourgeois and recur in her artistic

practice across seven decades. They vary from architectural forms to growth and germination

in nature, from the human body and sexuality to motherhood, and even include symbolic

abstraction. Her illustrated books bring attention to another of Bourgeois’s little-known

creative outlets: her highly evocative writings, which form the texts for these volumes.

“Her prints and their evolving states of development are especially revealing as they provide

the opportunity to see Bourgeois’s imagination unfold,” says exhibition curator Deborah Wye.

“To view such sequences is akin to looking over the artist’s shoulder as she worked.”

The creation of multiple examples of the same composition is fundamental to printmaking,

and this encouraged Bourgeois to re-envision her imagery in myriad ways by embellishing her

prints with gouache, watercolor, pencil, and ink to reflect her changing moods. She also

benefited from printmaking’s collaborative nature, which often entails the encouragement of

publishers and the assistance of expert technicians. Bourgeois’s printmaking relationships

could lift her spirits, and the work she accomplished with her collaborators in her

home/studio on 20th Street in Manhattan was creatively energizing.

The entire body of Bourgeois’s printmaking comprises some 1,200 individual compositions,

and constitutes a major component of her work overall. She created prints in two periods of

her career.

In the 1940s, she was an active printmaker and painter; she transitioned to

sculpture only late in the decade. At that time, while raising three small children, she often

made prints at home on a small press. She also frequented Atelier 17, a renowned print

workshop that had relocated from Paris to New York in the war years. When Bourgeois turned

definitively to sculpture, she left painting behind, but returned to printmaking many decades

later, in the late 1980s. During the 1990s and 2000s?when Bourgeois was in her eighties and

nineties?she made prints a part of her daily practice. She resurrected her old printing press

from the 1940s, and eventually added a second, both located on the lower level of her

home/studio.

The thematic sections of this exhibition bring together prints from both periods of

Bourgeois’s engagement with the medium. They also include related sculptures, drawings,

and early paintings, to underscore her overarching concerns. She saw no “rivalry” between

the mediums in which she worked. Instead, she said, they allowed her “to say same things, but

in different ways.”

Architecture Embodied

In pursuit of emotional balance and stability, Bourgeois often made use of visual symbols

derived from architecture. Her early study of mathematics may have attracted her to the

rationality of the built environment. Yet the idiosyncratic structures she created often exhibit

human features or reflect personal vulnerabilities. In prints and in early paintings, they

become “actors” in invented narratives, sometimes standing alone, but also interacting in

pairs or groups, as in the illustrations for her celebrated book He Disappeared into Complete

Silence. Architectural structures and room-like chambers could express safety and refuge for

Bourgeois, but also entrapment, as seen in her early Femme Maison imagery or her later

sculpture Cell VI.

Abstracted Emotions

Bourgeois is best known for huge Spider sculptures and provocative figures and body parts,

but her art also incorporated abstract forms throughout her long career. Straight lines,

curves, circles, grids, and an array of biomorphic formations are found in all the mediums in

which she worked. In Lullaby, her array of abstract shapes superimposed on the horizontal

lines of music staves conjures up an imagined musical score. Bourgeois employed such forms

for the function they served within a complicated psychological domain. Abstraction could be

calming, with repeating forms or strokes, or offer a sense of stability through geometry, but it

also expressed tension and anger.

Fabric of Memory

Bourgeois was raised in a family of tapestry restorers, but introduced fabric into her art only

when she reached her eighties. Deciding she no longer needed all the clothes she had saved

for years, or the household fabrics she stored, she began to incorporate dresses, slips, and

coats within her sculptures, and to cut up cloth for stuffed figures and patterned collages.

Bourgeois also began to make prints on fabric, enjoying the tactile qualities of the surfaces

and the way they absorbed ink. She went on to create fabric books, such as Ode a l’Oubli,

using old linen hand towels from her trousseau as pages, filled with abstract designs made

from bits of garments.

Alone and Together

Throughout her career, Bourgeois employed the human figure as self-portraiture, as seen

here in the provocative Sainte Sebastienne. She also depicted her relationships with others

through figurative symbolism, such as the representations found in Self Portrait, which

features one of her sons between his two parents. The figure, she said, helped “dissolve or

appease my anxiety,” and her highly inventive imagery often combines elements of the real

and the surreal. After intense psychoanalysis in the 1950s and 1960s, Bourgeois turned more

directly to the physicality of the body, including an explicit sexuality; she examined a

female/male continuum, and interactions between men and women. She also explored

motherhood, from birth to its inevitable interdependencies.

Forces of Nature

Bourgeois was a keen observer of nature from childhood on, and was familiar with a wide

variety of plants, flowers, shrubs, and fruit-bearing trees. Although she lived in New York as an

adult, she spent summers at a country house in nearby Connecticut. There, as a young

mother, she enjoyed interacting in nature with her three sons. In her art, she often found

human correspondences in such elements as wind, storms, and rivers, or seeds and

germination. And she related the body to the topography of the Earth, expressing an ongoing

mutability between natural and bodily forms, as evident in the undulating hills of Lacs de

Montagne ("Mountain Lakes").

Lasting Impressions

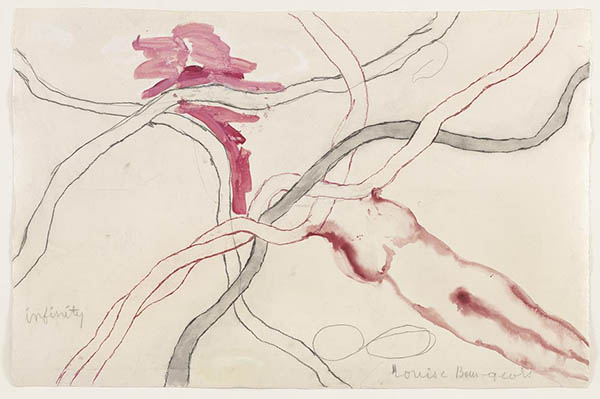

In the last years of her life?between the ages of 94 and 98?Bourgeois developed a highly

innovative form of printmaking on a large scale, with the soft ground etching technique and

extensive hand additions with brushes and pencils. The exhibition features the installation set

A l’Infini, a landmark of that period, demonstrating what might be characterized as

Bourgeois’s final “late style.” Here she creates a spontaneous, flowing, and tumultuous

abstract world, suggesting primordial beginnings. Babies, a nude, and an entangled couple

emerge from this whirling domain and call to mind many earlier figurative works by the artist,

such as the bronze Arch of Hysteria.

Marron Atrium Installation

A series of large-scale soft ground etchings, completed when Bourgeois was in her midnineties,

represents a period when her printmaking flourished. These works exhibit one of her

singular visual strategies: the creation of highly suggestive yet abstract forms. They also

highlight a recurring theme of the natural world, with curvilinear lines and organic shapes

calling to mind seeds, roots, vines, flowers, hanging fruit, and sheaves of wheat, while

sometimes hinting at parts of the body. One such example is Accumulations. The spider is a

creature of nature that Bourgeois called “a friend” when it caught bothersome mosquitoes.

But she also saw this crafty arachnid in symbolic terms, as representing her mother, a

tapestry restorer. That reference is vividly represented in the exhibition by her massive Cell

sculpture, Spider.

Audiovisual Components

Bourgeois’s recording Otte is presented at the entrance of the exhibition. She sings her own

invented lyrics?wordplays on French words and their masculine and feminine endings. To a

rap beat, she contrasts the power of men and of women as communicated by the structure of

language.

The exhibition also features a film clip from Louise Bourgeois: La Riviere Gentille, showing

Bourgeois with Ode a l’Oubli, a fabric book she made in 2002, with pages made from

monogrammed linen hand towels saved from her trousseau. (She married in 1938.) She filled

this book with fabric collages made from bits and pieces of her old garments; stains,

scorches, and cigarette burns testify to their histories. In the clip, Bourgeois is seen turning

the book’s pages, patting and smoothing them as she views the volume from beginning to end.

The film will be on view alongside the fabric book.

Bourgeois Archive at MoMA and Online Catalogue Raisonne

In 1990, Louise Bourgeois promised an archive of her printed art to the Museum, consisting

of all the prints and illustrated books in her possession at that time, and the promise of an

example of each new print going forward. MoMA now has in its collection some 3,000 printed

sheets by the artist, a unique resource for the study and understanding of her artistic vision

and creative process.

This vast archive of Bourgeois’s prints, as well as all others she created in the medium, is now

accessible online through the highly innovative, interactive website Louise Bourgeois: The

Complete Prints & Books (moma.org/bourgeoisprints). Edited by Deborah Wye, this site

presents Bourgeois’s work thematically, placing her prints in the context of related

sculptures, drawings, and early paintings. It also offers numerous access tools, including

searches by chronology, technique, format, publisher, and printer. Special features allow for

comparing works and zooming in on details. The website will be available to Museum visitors

during the course of the exhibition at a special computer kiosk and seating area.